MoSCoW prioritisation is on effort

One misunderstanding that I’ve encountered a lot over the last couple of years in relation to DSDM agile project management is in the area of prioritisation, and in particular how MoSCoW prioritisation works. In this post I hope to make things a little clearer

What is fixed?

In all projects you have, broadly speaking, four variables:

- Features

- Quality

- Time

- Cost (resource)

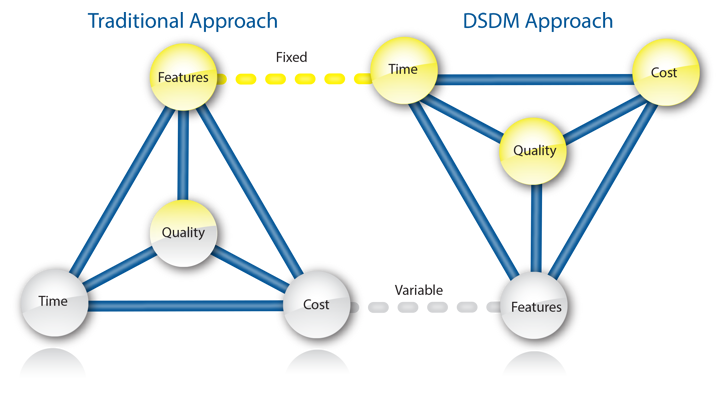

In traditional projects, as it is assumed that all requirements will be delivered, features are fixed. So, time, cost and to an extent quality are therefore variable. Which makes sense, if things are more complex than at first anticipated, in order to deliver all the features then you will need to give the project more time and/or money.

DSDM takes a different approach. This methodology argues that surely not all requirements can possibilty be of equal importance, and so DSDM argues for fixed time, fixed resource, and fixed quality, and it has developed a method for managing a variable set of features: MoSCoW.

MoSCoW prioritisation

MoSCoW is a handy acronym to remember the four categories of prioritisation: must, should, could and won’t (this time).

- Must — Without these the product will not function, be legal, or will be unsafe. This is often given the ‘backronym’ Minimum Usable SubseT.

- Should — Important but not critical to the project; it may be painful to leave them out, a workaround may be required, but the product will still be viable.

- Could — Nice to have but if left out will create less of an impact than if a should is omitted

- Won’t — These are the requirments which it has been agreed will be omitted entirely from either the whole project, or at least this increment or iteration.

In timeboxes (sprints) it is requirements marked as ‘could’ that create the main source of contingency. If something happens that puts the deadline at risk, it is from the pool of coulds that requirements get dropped first.

And if things continue to go badly then once the coulds have been depleted you can then start dropping shoulds.

This way, you guarantee that all the must-have requirements will be delivered.

60/20/20

DSDM is also quite opinionated on how to organise your timeboxes, so there is a realisitic balance of musts, shoulds, and coulds.

It would make no sense to work only on must-have requirements during a sprint — there would be no contingency, unless you can guarantee that your estimates are 100% correct. So DSDM recommends a balance of:

- 60% must-have effort

- 20% should-have effort

- 20% could-have effort

But this is where I have encountered the most confusion when dealing with MoSCoW. I have been in planning sessions with Agile project managers and business analysts who have tried to make sure that 60% of the requirements are categorised as musts, 20% as shoulds, and a further 20% as coulds.

In other words, let’s say we have a project with 100 requirements — they have tried to ensure we have 60 musts, 20 shoulds and 20 coulds.

While this could potentially be a useful exercise while gathering requirements, to reinforce to stakeholders that not everything is a must-have, when it comes to timebox planning this isn’t what the DSDM guidelines recommend.

This is what the DSDM Handbook says:

On a typical project, DSDM recommends no more than 60% effort for Must Have requirements on a project, and a sensible pool of Could Haves, usually around 20% effort.

The thing to notice here is the word ‘effort’.

What is effort?

Effort, of course, means the amount of work required to complete a task.

In Agile projects we often estimate in either ideal time or story points. Ideal time (measured usually in hours or days) is an estimate of how long a task will take to complete assumeing it’s all you work on, you have no interruptions, and everything you need is available). Story points are an arbitrary measurement used to estimate the size of tasks relative to one another; they often use an adjusted Fibonacci sequence (0, ½, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 20, 40, 100 plus ∞).

Example

So, let’s take as an example, a very small, very simple project that has only 10 requirements, which are written in Latin, not because we’re St Andrews but so you don’t get distracted reading them.

1. Gather requirements and priorities

Here is our list of requirements:

| ID | Description | Priority |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lorem ipsum dolor | Must |

| 2 | Sit amet | Must |

| 3 | Consectetur adipisicing elit | Should |

| 4 | Fuga sapiente, nulla facere | Could |

| 5 | Eaque molestias similique | Could |

| 6 | Cupiditate error voluptas! | Could |

| 7 | Fugit, quasi aliquid | Must |

| 8 | A quas ea rerum | Must |

| 9 | Quis ipsam illo | Should |

| 10 | Dolorem fuga | Should |

As you can see, when we gathered these requirements from our business stakeholders, we also asked their opinion on prioritisation.

In their opinion what would be the minimum usable subset of features required to create a successful product? And which requirements might be regarded as nice-to-haves that have painful workarounds (shoulds) and easy workarounds (coulds)?

2. Estimate requirements

At this point, we have no indication of the effort required to deliver these requirements.

So we now meet with the solution development team to gahter from them their estimates on how long each feature will take to develop. Here we are using story points.

| ID | Description | Priority | Estimate |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lorem ipsum dolor | Must | 3 |

| 2 | Sit amet | Must | 8 |

| 7 | Fugit, quasi aliquid | Must | 20 |

| 8 | A quas ea rerum | Must | 13 |

| 3 | Consectetur adipisicing elit | Should | 8 |

| 9 | Quis ipsam illo | Should | 5 |

| 10 | Dolorem fuga | Should | 13 |

| 4 | Fuga sapiente, nulla facere | Could | 8 |

| 5 | Eaque molestias similique | Could | 8 |

| 6 | Cupiditate error voluptas! | Could | 5 |

| Total | 91 |

We can see that the total effort to deliver the entire product is equal to 91 story points.

3. Team velocity

We are almost there, but before we can begin to plan our timeboxes, to determine what gets developed when, we first need to have an idea of our team’s velocity.

Velocity is the term used to measure how many story points a team can comfortably complete in one iteration (one sprint, if you are using Scrum terminology).

Let’s assume that our team can comfortably complete 32 story points each iteration.

We now know, that if all goes well we should be able to complete all these requirements within three iterations (sprints):

91 story points / 32 story points per iteration = 2.8 iterations.

4. Use MoSCoW to plan iterations

We can now begin to organise the requirements into timeboxes, trying to keep as close to these limits of 60% must-haves, 20% should-haves and 20% could-haves as we can, so that we build into each iteration some contingency.

Remember, we’re working this out on effort. So, if we can complete 32 story points each iteration we can work out that:

- 60% of 32 = 19.2 story points

- 20% of 32 = 6.4 story points

This now gives us a useful guide: aim for about 20 story points for must-have requirements, and around 6 story points for both should-have and could-have requirements.

The task of actually working out what goes into each iteration is often more of an art than a science. It is not always easy or straight-forward. You may have to take into account things like how often you plan to deploy, project dependencies, resource availability, etc. I often use post-it notes or spreadsheets to work out iteration plans.

So, here’s how we might organise these

Iteration 1

| ID | Description | Priority | Estimate | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | Fugit, quasi aliquid | Must | 20 | 62% |

| 9 | Quis ipsam illo | Should | 5 | 16% |

| 6 | Cupiditate error voluptas! | Could | 5 | 16% |

| Total | 30 | 94% |

Iteration 2

| ID | Description | Priority | Estimate | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | A quas ea rerum | Must | 13 | 40% |

| 3 | Consectetur adipisicing elit | Should | 8 | 25% |

| 5 | Eaque molestias similique | Could | 8 | 25% |

| Total | 29 | 90% |

Iteration 3

| ID | Description | Priority | Estimate | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 2 |

Lorem ipsum dolor Sit amet |

Must Must |

3 8 |

34% |

| 10 | Dolorem fuga | Should | 13 | 41% |

| 4 | Fuga sapiente, nulla facere | Could | 8 | 25% |

| Total | 32 | 100% |

As you can see, we have not been able to stick exactly to 60% musts, 20% shoulds, and 20% coulds. But in each iteration we have built in enough contingency to allow us to drop features if required without compromising the success of the whole project.

You can also see that, apart from in the final iteration, we have also built in some ‘slack’ (6% in the first iteration, and 10% in the second). Slack in Agile is basically unassigned time that allows some breathing space for tasks that may take a little longer than estimated. This is an additional type of contingency that we’ve built into the iteration plan.

Conclusion

MoSCoW prioritisation is a very useful tool for ensuring that quality, time and resources are fixed to ensure that the right product is developed on time.

Be aware, however, that if you use MoSCoW prioritisation that the balance of 60% must-haves, 20% should-haves, and 20% could-haves are made on the estimated effort (time) of requirements and not simply on the total number of requirements.